In Calvin and Hobbs, Calvin’s dad tells Calvin ‘The World isn’t fair , Calvin’. To that, Calvin responds,’ I know but why isn’t it ever unfair in my favour?’

In legal practice, clients who feel they had been wronged, they exclaim, ‘Surely there must be justice. Aren’t there laws?’

Laws are made to keep order in the society, and also to protect individuals and groups against human rights abuses. We talk about equal opportunities to all regardless of one’s gender or ethnic group. But there are no laws to state that love is equal regardless of who you are and where you come from. There is no right or wrong when you love someone but when it is the wrong time or the wrong place, there will be undesirable consequences that will not end well.

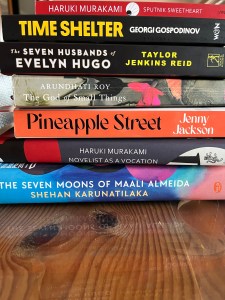

In The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, two fraternal twins are desperate for love. Their mother, Ammu marries their father to escape from her home. She subsequently divorces the husband who turns out to be an alcoholic and a liar. When Ammu brings her six- year-olds back to her family in Ayemenem,Kerala, they are unable to make friends due to the social stigma of Ammu’s divorce. Esthappen Yako and Rahel have no surname because Ammu is considering reverting to her maiden name. To her, choosing between her husband’s name and her father’s name does not give a woman much of a choice. They are descendants of the Ipes who are a wealthy Syrian Christian family. Ammu’s father, Pappachi insists that a college education is an unnecessary expense for a girl, getting married becomes the only option for her to escape from her ill-tempered father and her bitter and long-suffering mother. When she meets her future husband at someone’s wedding reception, she accepts his proposal after only knowing him for four days. Now that she is twenty-seven, ‘she carried the cold knowledge that for her, life had been lived. She had had one chance. She made a mistake. She married the wrong man.’

Her elder brother, Chacko was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford and is permitted excesses and eccentricities nobody else is .He is also divorced. He had married Margaret, an English woman who divorced him to marry Joe. To Ammu, her brother has never stopped loving his ex-wife. When Joe dies, Margaret and her daughter, Sophie Mol is invited back to Ayemenem. The twins are in awe of all that preparation and fuss about the arrival of their English aunt, Margaret and their nine-year-old cousin,Sophie Mol from London. ‘It had been the What Will Sophie Mol Think?week.’ When their guests arrive, During Sophie’s stay, one day she joins the twins on a boat found by Rahel and fixed by Velutha whom the children love as he makes toys for them. The boat capsizes and Sophie drowns. What follows the calamity is grief. As gloom looms in the air, things get worse, and now the Terror.

Ammu has fallen in love with Velutha. He is a Dalit – a member of the caste formerly called Untouchable. The romance between Ammu and him has to be kept secret. Unfortunately Velutha’s father finds it his duty to tell Ammu’s mother,Mammachi about what his son’s transgression. He has felt indebted to Mammachi for having paid for his glass eye and ‘his gratitude to Mammachi and her family for all that they had done for him was as wide and deep as a river in spate.’

Vellya Paapen is an Old World Paravan. The Terror takes hold of him and he asks God’s forgiveness for having spawned a monster and he even offers to kill his own son.

He has once feared for Velutha, his younger son whose qualities might have been befitting and even desirable for Touchables but could be construed as insolence for them. When he cautions his younger son, his good intentions drive him away for a few years. Velutha finally returns after hearing about his older brother’s fall that has crippled him. Velutha possesses natural skills and talents since very young age. When he returns, he is rehired by Mammachi as a carpenter and he is put in charge of general maintenance in Paradise Pickles and Preserves, a business started by Mammachi and expanded by Chacko. Now that Velutha and Ammu have breached the Love Laws, with meddling family members, his romance with Ammu will only end in catastrophe.

‘They broke the Love Laws. That lay down who should be loved . And how. And how much.’

The God of Small things is a complex story that deals with struggles of women and individuals from lower caste and at the centre of it, it is a story about Estha and Rahel and their mother who is powerless in a patriarchal society. Its author, Arundhati Roy has clevery put together a complex story that spans from 1969 and 1993.

It is 1993, Rahel returns from America to the Ipes’s Ayemenem house in Kerala as a grown adult. Chacko has emigrated and every other family member has passed on except for her grandaunt, her grandfather’s younger sister who was known as Baby Kochamma. She has not come home to see her eighty-three year old grandaunt whose real name was Navomi Ipe but everyone called her Baby. Rahel has come home to see her twin brother, Esthappen, who was born eighteen minutes before she was born. They have been separated for twenty-three years since Sophie’s tragic death. Their mother has to send Estha to his father and now his father has moved to Australia, Estha is re-returned to Ayemenem. Ammu dies at thirty-one.

Here is how Roy has described the twins.

‘They were two-egg twins. ‘Dizygotic’ doctors called them. Born from separate but simultaneously fertilized eggs.‘

Even when they were thin-armed and flat-chested children, they never did look much like each other. ‘There was none of the usual’ Who is who?’ and ‘Which is which?’ from oversmiling relatives or the Syrian Orthodox Bishops who frequently visited the Ayemenem house for donations. ‘

Before Estha and Rahel had ‘thought of themselves together as Me, and separately, individually, as We or Us. As though they were a rare breed of Siamese twins, physically separate, but with joint identities‘. Now ‘their lives have a size and a shape now. Estha has his and Rahel hers.’

Estha has stopped talking altogether. It has happened gradually and it is as though he has simply run out of conversation. No one can ‘pinpoint with any degree of accuracy exactly when (the year, if not the month or day) he had stopped talking.’

His quietness does not feel invasive. He occupies very little space in the world.

‘The room had kept his secrets. It gave nothing away. Not in the disarray of rumpled sheets, nor the untidiness of a kicked off shoe, or a wet towel hung over the back of a chair. Or a half-read book. It was like a room in a hospital after the nurse had just been. The floor was clean, the walls white. The cupboard closed. Shoes arranged. The dustbin empty.

The obsessive cleanliness of the room was the only positive sign of volition from Estha. The only faint suggestion that he had, perhaps, some Design for Life. Just the whisper of an unwillingness to subsist on scraps offered by others. On the wall by the window, an iron stood on an ironing board. A pile of folded, crumpled clothes waited to be ironed.

Silence hung in the air like secret loss.’

In The God of Small Things, the events are not told chronologically thus it is not an easy read. You gather the story as you patch together the flashbacks that are mostly revealed as memories through Rahel’s eyes. As the narrative unfolds, you gain insights into the characters and happenings and its intensity tugs at your heart. The God of Small Things was awarded the Booker Prize, 1997. It is a complicated and compelling story. The tragic tale is about forbidden love, class divisions and gender inequality. Its prose is undeniably rich and beautiful. Arundhati Roy is a gifted writer.