Literature has to be timeless not fleeting.I try to read an array of fictions, contemporary, classic, crime, science, speculative, historical and novels with a myriad of genres such as The Unconsoled by Kazuo Ishiguro and The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster. I enjoy reading prolific writings by Julian Barnes with his personable and yet slightly distanced tone and the premise of his stories is about reliability of memory, love and close relationships. The Sense of Ending is brilliant. Invariably, all the reads are about the human heart hence the conflicts that give rise to these stories. I also enjoy reading autofictions, e.g. Kudos and Transit by Rachel Cusk. Deborah Levy‘s series of memoirs entitled ‘living autobiography’ : Things I Don’t Want to Know (2013), The Cost of Living (2018) and Real Estate are memoirs that I would like to read again one day. I enjoy Levy‘s allusive and dreamlike writing when she muses about life, gender roles, marriage and memories from her childhood.

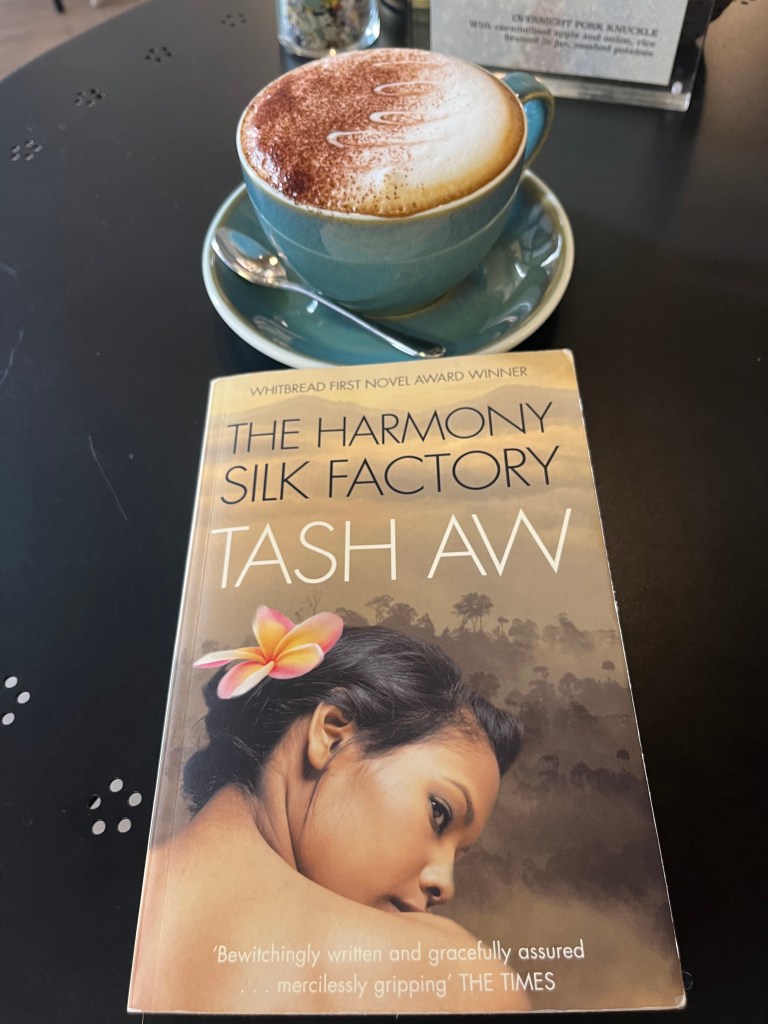

The Harmony Silk Factory written by Tash Aw is first set in the 1940s when the Japanese is about to invade Malaya. Johny Lim , textile merchant , a notorious man who started out as a small village peasant boy has now become the richest man in Kinta Valley near Ipoh, Malaya. The Harmony Silk Factory is Tash Aw‘s debut novel.

There are a few underlying themes in the story. At the outset, it is a story about the elusive character, Johny Lim formerly known as Lim Seng Chin. He is viewed from the vantage points of three unreliable narrators respectively, Jasper his only son, Snow Soong, his beautiful wife and Peter Wormwood, an eccentric British man. The harmony silk factory is a textile shop that Lim acquired in 1942 and the Lim family lives in a house separated from the factory.

His son, Jasper, now in his forties, regards his father as a villain. Growing up, he was fearful as well as in awe of his father. He was aware of all the illegal activities such as smuggling drugs and hard liquor for selling on the black market in Kuala Lumpur. He has put his ‘crime-funded education to good use‘, reads every article in every book, newspaper and magazine that mentions his father to understand what happened and to be able to relate the truth of his father’s life. To Jasper, Johny was many things, a father, a husband, a killer, a communist, a smuggler and a traitor.

When the son turns up for Johny’s funeral, his arrival is greeted with some relief. His father’s closest friends, old business partners take charge of the funeral arrangement, they have ‘ordered the most elaborate and expensive offerings they can think of, the grandest luxuries fit for a man of Father’s standing‘ Aside from a paper Mercedes-Benz with a paper chauffeur sitting at its paper wheel, there is also a paper aeroplane, a Boeing 747.

In Jasper’s voice,

‘The funeral of a traitor is a tricky thing, particularly if that traitor was someone close to you. You may be tempted, as I was ,to avoid it altogether as a sign of protest at the crimes, as I was , to avoid it altogether as sign of protest at the crimes that person has committed. But if that person is your father and you are his only son, you have no choice. If no one else knows that he was a traitor, then your protest becomes meaningless. So I stood alone throughout the three- day ceremony, locked away with only my terrible, secret knowledge for company.’

‘ Many hundreds came to pay their respects. All kinds of people turned up- princes, peasants, politicians, criminals, pensioner, toddlers. They travelled from afar afield, from the remotest reaches of the country, and some even came from abroad.There were mourners from Hong Kong and Indonesia and Thailand, together with the odd Filipino. A few white men were there too, though where they were from was anyone’s guess. One of them was an Englishman, I think, though he was so old it was difficult to tell. He sat folded over in a wheelchair, barely able to move amid the crowd of bodies, looking lost and confused. He seemed not to be able to speak, though occasionally he coughed and wheezed a few curious sounds.’

Jasper asks who the man is. Auntie Siew Ching now known as Madam Veronica thinks the old Englishman’s name in the wheelchair is Peter or Philip. The old Englishman presents Jasper a parcel wrapped in its silken cloth. Inside the parcel lies a journal that belonged to Jasper’s mother.

Part Two of the story comprises of Snow’s journal.

In her diary, Snow writes about how she was first attracted to Johny who is very unlike anyone she knows. But now she is thinking about leaving him. Snow diarizes about the trip purportedly their belated honeymoon that she and Johny Lim has taken in the company of three chaperones, Peter Woodworm the vagabond, Frederic Honey a self-important mine supervisor and the Kunichika Mamoru, the Professor who turns out to be the military attaché to the region. She has found a piece of waxcloth in Johny’s things and uses it to wrap the diary in it so ‘it will be kept safe from the sea and all the things that lurk in its depth‘.

The entourage sets out onto the Straits of Malacca in the boat ‘Puteri Bersiram (‘The Bathing Princess’)without a boatman. They venture to navigate their way to the Seven Maidens and along the journey, their boat breaks down. It is a treacherous adventure. In her diary, she is steeling herself to tell Johny that she wants a divorce.

From Jasper’s account, we know that Snow died on the day he was born. Snow Soong was the only daughter of Scholar and Tin Magnate TK Soong. She was only 22 when she passed away.

Part three entitled The Garden is where Peter, now in his old age, tells of his excursion to the land of Orient and he is now in a care home for the aged in Malacca. He is eccentric and known as the Mad English Devil at the home where there are ‘twenty-two rooms occupied by twenty-two near-fossils, little more than a halfway house in the short journey to the cemetery down the road‘. He has never been entirely certain of the accuracy of the translation of his nickname from the Chinese.

He sounds pompous. In his voice,

‘I suspect that Alvaro politely edited the fruitier connotations from the original phrase when he translated it for me. He has this poorly conceived notion that I am to be pitied, being the lone foreigner in this place. And so he tells me things which I know to be untrue- compliments people supposedly pay me, words of admiration, always in Chinese, or Malay, or Tamil. Of course, one must take everything he says cum grano salis.

It’s only reasonable to expect, I hear you cry, that I should have some knowledge of Chinese after all these years, but I don’t. Not a bit. I have always detested the language; I find it so trenchant. And superfluous too, seeing as everyone speaks English – or some form of it-anyway. No, after sixty years of living here, the process of linguistic osmosis hasn’t worked in the way you’d assume – in fact quite the reverse has happened : I have remained wonderfully impervious to Malay and Chinese, but my English, dear God, has been leeched out of me. Some days I can hardly speak.’

Peter wants to introduce some plants into the garden. He is told that it is inappropriate to plant frangipani tree in a Malaysian garden and is met with resistance as he plans to plant frangipani at the care home’s new garden:

‘ “It’s the tree of death,”[Alvaro] said. “Muslims plant it in their cemeteries.”

“Superstitious claptrap,” I said. “The country is riddled with it… The Siamese at least have a decent excuse for not wanting it in their back gardens. Their word for chempaka is virtually the same as that for “sadness”. But that doesn’t stop them from planting it in a monastery and temple gardens…”’

Peter narrates how he fist met Johny in Singapore when he decided to leave England with the hope to find his paradise in the orient. In his words,

‘ My Singapore was to be found in the alleys of Bugis Street and Chinatown, where shopkeepers recognised me and gave me cups of sweet coffee at three o’clock in the morning. All life – all real life -gathered there after dark, and strangers found solace in each other’s company. Merchants, prostitutes and scholars moved as equals in this place. I would sit all night watching the va-et-vient of Lascars and madmen; I was alone but never lonely. And it was here, at precisely eleven o’clock one evening, that I met Johny.’

He was surprised to find Johny reading ‘Shelley’ in a corner of the coffee shop at the end of Cowan Street. He describes Johny as having ‘the silent, easy grace of a Balinese nobleman of the type depicted in lithographs of sumptuous palaces‘. ‘When he smiled his face transformed into that of a child – radiant, innocent, happy.’

Johny then explained that he was married and his wife spoke English. He was trying to improve his English so that he could converse freely with her and her family. Peter told him that he would teach him everything he needed to know. Johny disclosed that he was from the Kinta Valley. Johny left Singapore the next day. Peter wanted to see him again so he set out to the Kinta Valley. And there he found Johny in Kampar. They became friends.Johny was keen to show Peter the valley, in return, Peter would answers the questions that Johny asked.

Peter tells about how inquisitive Johny was .

‘What is the meaning of “expostulation?” Who was Ozymandias, actually?'”Was Hamlet really crazy?’What is the difference between “toilet” and “lavatory”?‘

He drank my answers as if quenching an ancient thirst. ‘

When Johny fired too many questions, Peter made up stories fom a glittering past he never knew he had.

From Peter’s account, we see that Johny was just a man eager to fit in and he had thought he had found someone to talk to not knowing that Peter would also betray him.

Peter laments,

‘Many times I have analysed that strange moment, carefully unweavmg the richly twisted strands of emotion that ran through my nerves as I stood watching Johny, poor wonderful Johnny standing on the slope of that hill.As the fabric of that memory comes apart in my hands, I see that the answer is really very simple. For those few seconds, I found myself looking into the face of a friend, the first and only one I would ever have, the only one I would ever love.’

But Peter was wrong about himself. He betrayed Johny by disclosing to Kunichika who Johny was and Kunichika was there to lay the groundwork for the Japanese to invade Malaya. I am not certain why Peter did that? Did Peter do that to get Johny to go to Singapore with him or to get Kunichika out because Snow was attracted to Kunichika and she would not heed his advice when he asked her to tread carefully with Kunichika?

The Harmony Silk Factory is history meets fiction. Tash Aw has weaved together a story that gives a rich description of colonial days, how the British treated and viewed the local people in Malaya, how they exploited the workers and that there were only a few schools founded by the British, reserved for the children of royalty or ruling-class Malays, civil servants and the sons of very rich Chinese. There is also story also places like Kinta Valley in the old days. Tash Aw is a sensitive writer. The Harmony Silk Factory is an ambitious debut in that there are three different and quite distinct voices that offer their different viewpoints. We have to piece together the story from three different voices where the narratives interweave between the past and the present hence the book can be quite an intense and challenging read as you try to figure out the loose ends. Nonetheless The Harmony Silk Factory is a fascinating read.